HERE I AM / NEVER ENOUGH TIME

is an interactive and immersive documentary about belonging within accidental, invisible, and institutionalized communities. Drawing from over three years of audio recordings (from oral histories with incarcerated men to soundscapes of the physics and perception of sound in prison), Here I Am seeks to bring together people distanced by time, identity, and location, yet unknowingly connected by place, memory, and experience (displacement, isolation, institutionalization). By studying the relationship between place, ‘destiny’, and desire, I aim to challenge the notion that we can ever disappear people and investigate our throwness (Heidegger's term to describe the arbitrary nature of "humans' individual existencess as being thrown into this world").

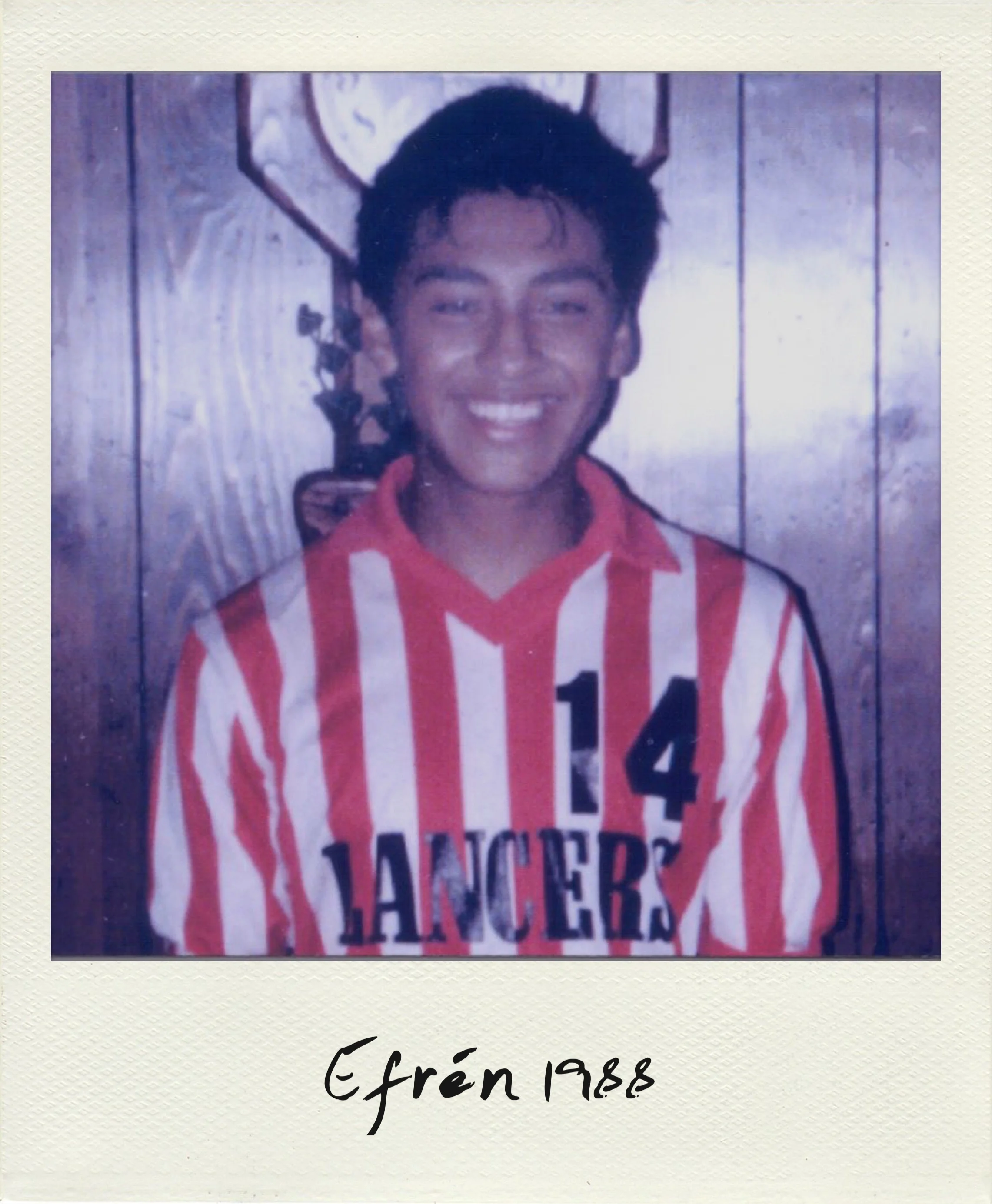

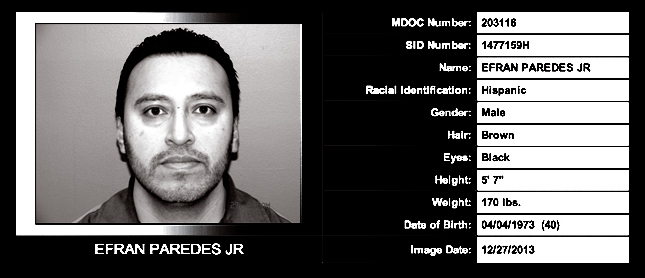

At the heart of this project, are two men who were sentenced to juvenile without parole (JLWOP), Efren Paredes Jr. (1989; MI) and Adolfo Davis (1991; IL) almost 30 years ago. Efren and Adolfo have been incarcerated for more than half of their lives and for my entire life. To challenge the narratives imposed upon them and one another, this project intimately invites you into their memories, current realities, and the communities and landscapes that they were displaced from.

I am hopelessly in love with a memory.

An echo from another time, another place. - Foucault

I have been recording the daily lives of Adolfo Davis and Efrén Paredes Jr. since 2015. On the phone, we talk about everything: from what music they are listening to that day, to the view outside of their window, to their interactions with guards, teachers, prisoners, and visitors. When I began this project, my aim was to document the barriers prisoners face to rehabilitate themselves in such a violent environment. Over time, I became interested in the perseverance of their hope. Curious as to what motivates them to fight for their freedom in such a hostile environment, I came to appreciate the role memory plays in their lives. By training themselves to focus on their memories, it's like the mind becomes a labyrinth -- to survive you have to create a world you can get lost in. Through maintaining relationships with their loved ones on the outside and producing work that immerses their voices in the world, they create meaning in the present and defy the monotony of a daily existence inside of a prison cell.

I chose to collaborate with Efren and Adolfo for several reasons:

they were both the youngest inmates in their respective states to receive a 'natural life' sentence

they have spent more than half of their lives in prison, including in solitary confinement

there is strong evidence supporting that they were wrongfully convicted

their cases are representative of the impact of racial bias in the criminal justice system; they were both convicted by white juries, prosecutors, and judges

they are both in the process of appealing their cases, and thus, need to demonstrate their transformation and engagement with the community to be considered for parole

they are experts on corruption in the criminal justice system and thus, expressed a strong desire to collaborate on a project that addresses the need to reform correctional facilities and policies from their experiences

The purpose of continuously conducting interviews with Efren and Adolfo on a daily to weekly basis, is to demonstrate their growth, and to thus challenge the belief (and prosecutors' claims) that anyone, especially juvenile lifers, can be irredeemable. To suggest that anyone is incapable of change or is irredeemable is a failure of the imagination. Through this work, I hope to cultivate compassion across disparate communities and landscapes and to provoke conversations about the need to design prisons to be places where prisoners can express themselves, learn, and maintain touch with outside world. The right to grow is necessary for prisoners to successfully rehabilitate and reenter their communities as contributing citizens.

This work is constantly evolving with Efren and Adolfo. It is both a temporal public exhibition ("Buried Alive", Columbia University 2018) and a series of published audio pieces and short films. Here you can get to know more about Efren and Adolfo, explore media from this project, and find information related to juvenile life without parole.

NATURAL LIFE SENTENCES

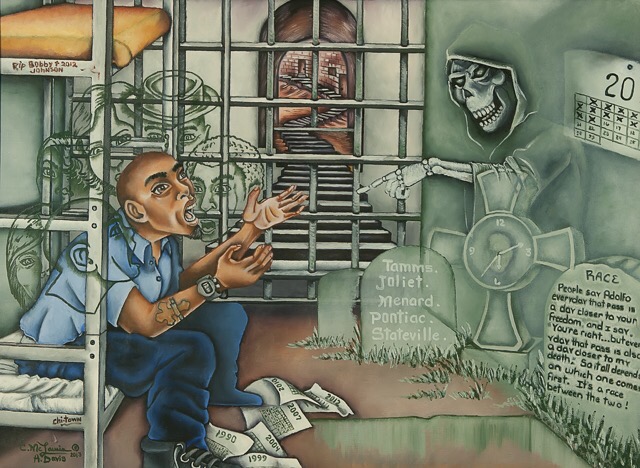

In US law, natural life is a legal term that describes how a life ends. For people who are free, to die naturally or of natural causes is a desired death— it’s the ending we wish to have after a life fully lived; a death caused by the inevitable dismantling of our bodies into invisibility. There is nobody to blame, no tragic accident nor sudden illness, nothing to push back against…. just the beautiful tragedy of being carbon that got lucky. On the outside, we are considered lucky to have a natural death, but on the inside, a natural life sentence is a sentence with endless distances. It is a sentence someone has to serve their entirety of their life. If you receive a natural life sentence, that means you are not eligible to even be considered for parole, probation, or suspension of sentence. It is a life where death stares at you in the face every day. It is a life that challenges the human instinct for survival.

Natural life is cold, lumpy oatmeal at 5:30 am.

Natural life is the colour and taste of concrete.

Natural life is stuffing toilet paper in your ears to block out the constant noise.

Natural life is being in your cell for count at 5am, 11am, 3pm, 7pm, and 10pm — no matter what.

Natural life is never being able to lay beneath the night sky and stare into the constellations again. It’s being afraid to sleep at night because sleep is too close to death.

Natural life is never being able to hold or be held by the person you love.

Natural life is not being trusted — it is everything you say or do being watched every moment for the rest of your life.

Natural life is being told that the world is not for you, anymore. That you are irredeemable.

Natural life is dying in a place where you will not be missed.

According to a new report issued by the Sentencing Project, nearly 162,000 inmates are serving a natural life sentence, or one out of every nine people in prison. In addition, 44,311 individuals are serving “virtual life” sentences of 50 years or more, a sentence in which it’s likely the person will die in custody. In the U.S., we don’t even really know how many people die behind bars each year — the data is incomplete and ambiguous. There is no streamlined data collection process that can be applied to collect data from state prisons, federal prisons, private prisons, and juvenile detention centers. Estimates suggest anywhere from 4,400 to 7,000 inmates die in jail and prisons every year. This does not count suicides. Yet, we continue to design prisons to be places that punish, instead of rehabilitate, people. To survive one must cultivate hope, or risk becoming institutionalized.

This is our criminal justice system.

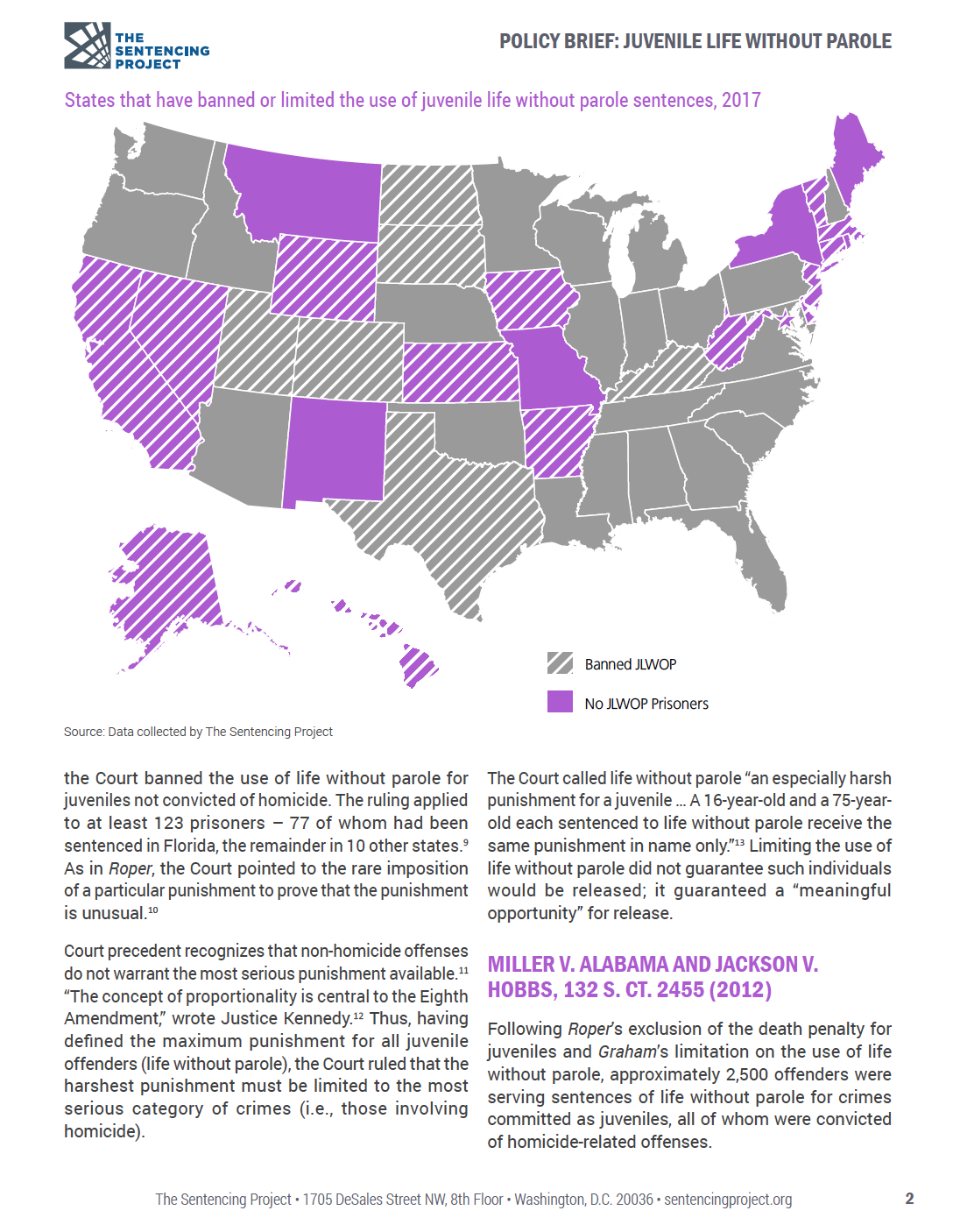

The United States is the only country in the world to sentence people to life in prison without parole for crimes they committed before they were 18. Most of the approximately 2,100 individuals sentenced as juveniles to life without the possibility of parole now have a chance for release in the wake of recent Supreme Court decisions. Twenty states and the District of Columbia have banned life sentences without the possibility of parole for juveniles; and in a several other states, no one is serving the sentence. At the time of his sentencing, Efren Paredes Jr., was the youngest person in in Michigan’s history to receive the sentence. Today, Michigan has the second highest number of people serving JLWOP sentence in the country, 346 people. In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama, that the federal government is required to consider the unique circumstances of each juvenile defendant in determining an individualized sentence.

In 2016, the Montgomery v. Louisiana decision, ensures that the decision applies retroactively. For juveniles, a mandatory life sentence without the possibility of parole is unconstitutional. This ruling was based on research which confirms the understanding that children are different from adults in ways that are critical to identifying age appropriate criminal sentences. If resentenced, juvenile lifers must demonstrate their capacity for change and contest their irredeemability, to become free.

EFREN PAREDES JR. (incarcerated March 1989 - today)

29 years ago,

Efren was convicted for the murder and armed robbery of Rick Tetzlaff, a manager at the grocery store where he was working as a bagboy. He was 15 years old and an honor roll student with no criminal record. Efren alleges that on the night of the crime, he was brought home by the store’s manager after completing an overtime shift. He came home, heated up a slice of pizza his mom left out for him, went up to his parent’s room to catch up about his day, and then went to bed. Meanwhile, the store was robbed and the manager was murdered.

Efren was charged with 3 life sentences and was the first teenager to be automatically sentenced to JLWOP in Michigan's history. There was no physical evidence linking Efren to the crime and no eyewitnesses. The case against Efren was based primarily on the statements of other youths who received reduced charges and sentences in exchange for their testimonies. Efren’s mother and his younger brothers all claim that they had witnessed his return home before the murder was committed. Those testimonies were discarded. Efrén was sentenced to two life without parole sentences and one parolable life sentence.

Efren was tried and convicted by a jury comprised of 11 White jurors and one Black juror by the Berrien County Court in St. Joseph, MI, which in 1989 had a population that was 95% white. The judge, prosecutor, all the investigating police, and the victim in the case were all white. All but one of the youths in Berrien County who have received life without parole sentences have been children of color.

Efren is still seeking exoneration. He expects to be resentenced in the coming months.

NEVER ENOUGH TIME

is a short, experimental radio and film piece about endless distances. Featuring the voices of Efren and his mother, Velia, Never Enough Time explores the long-distance relationships between the incarcerated and their loved ones and the costs of isolation [Time: 16:38].

This video is password protected. To watch this video, contact me at: elyse.blennerhassett@columbia.edu

Gallery

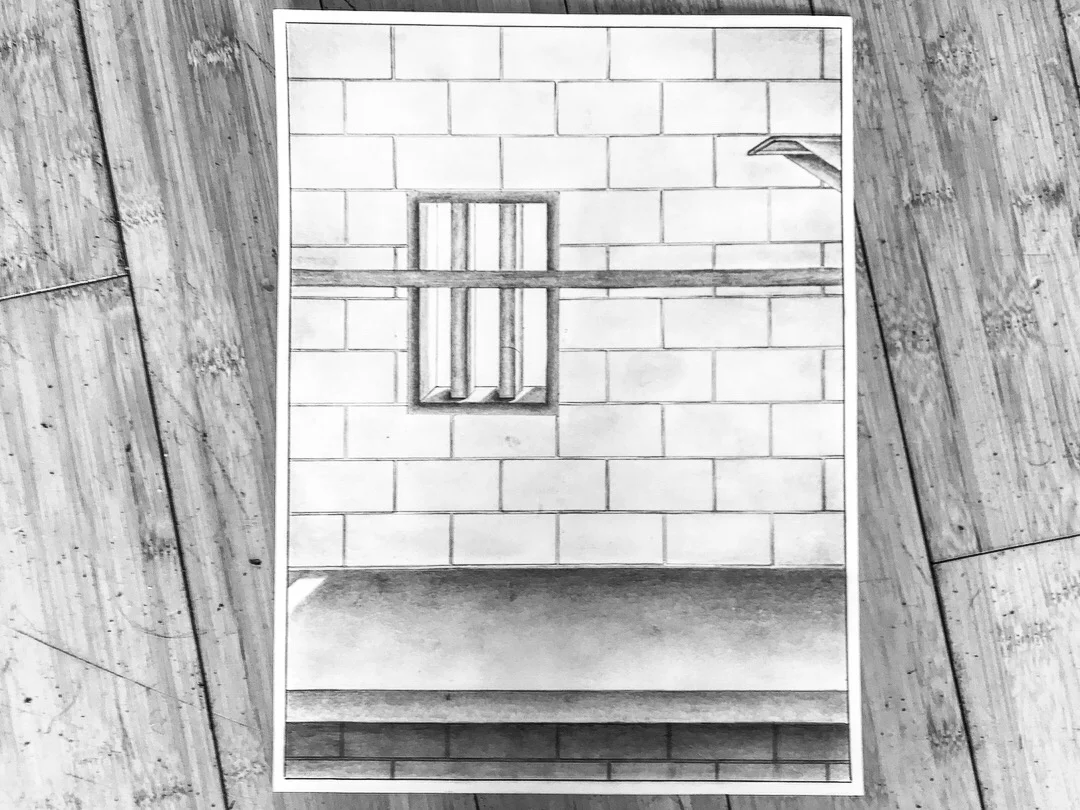

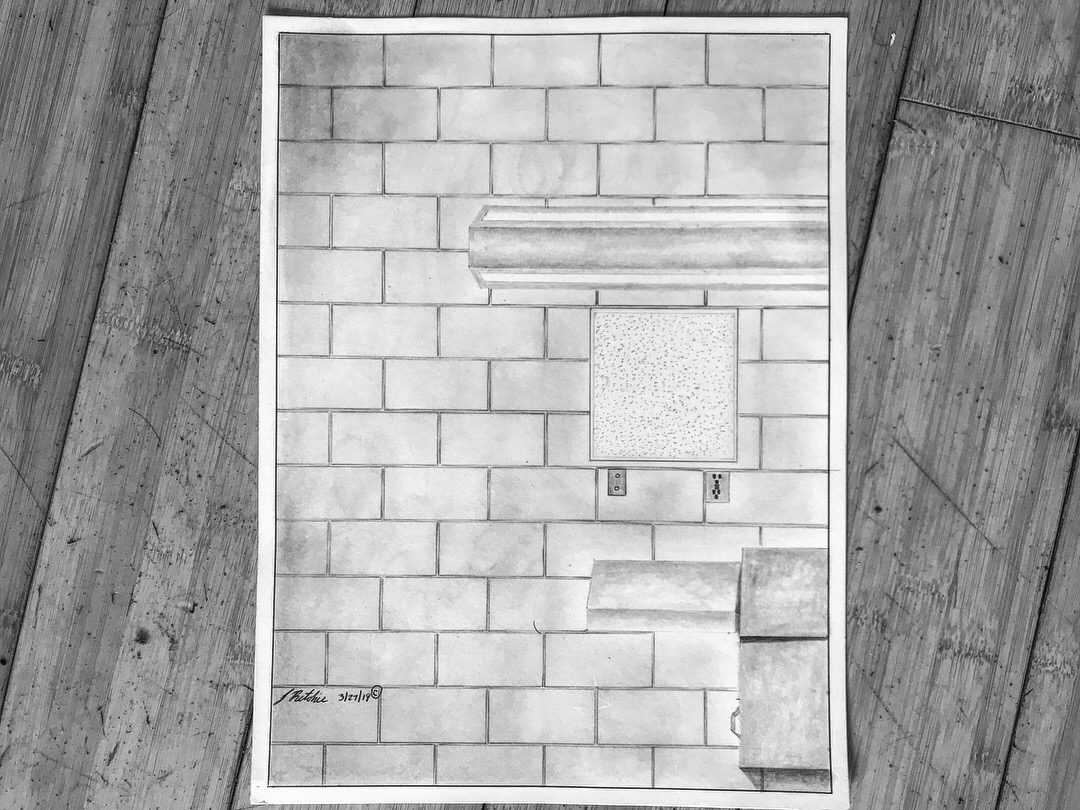

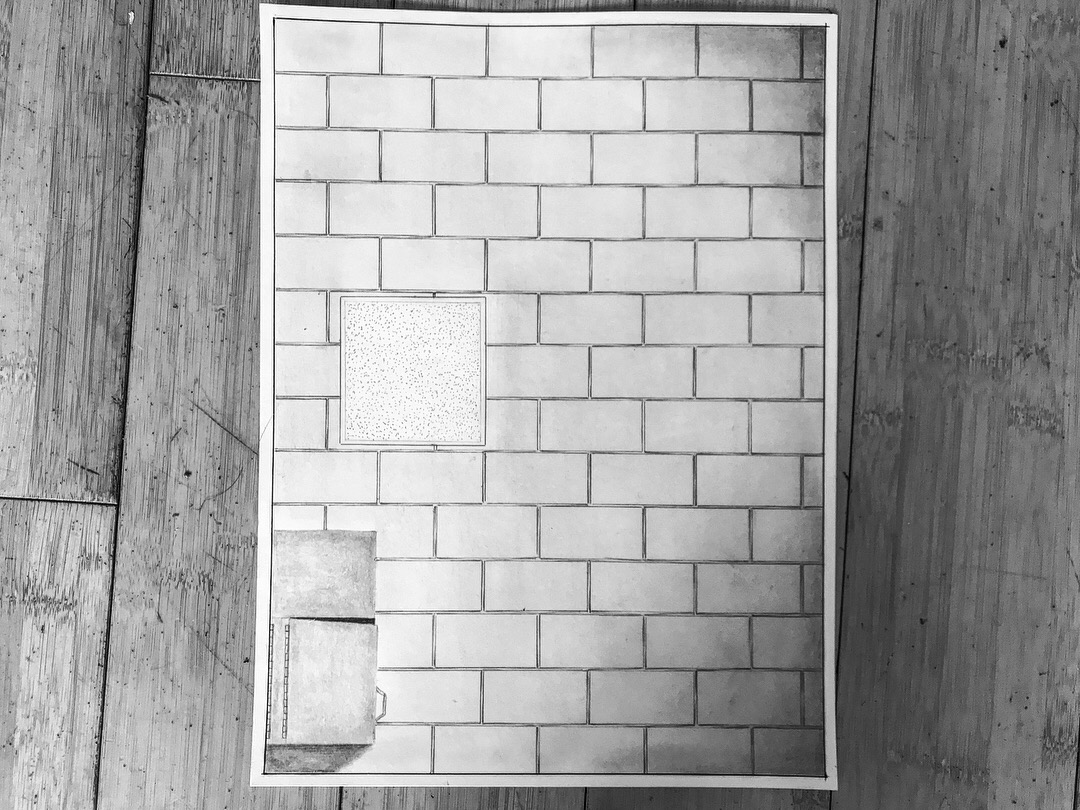

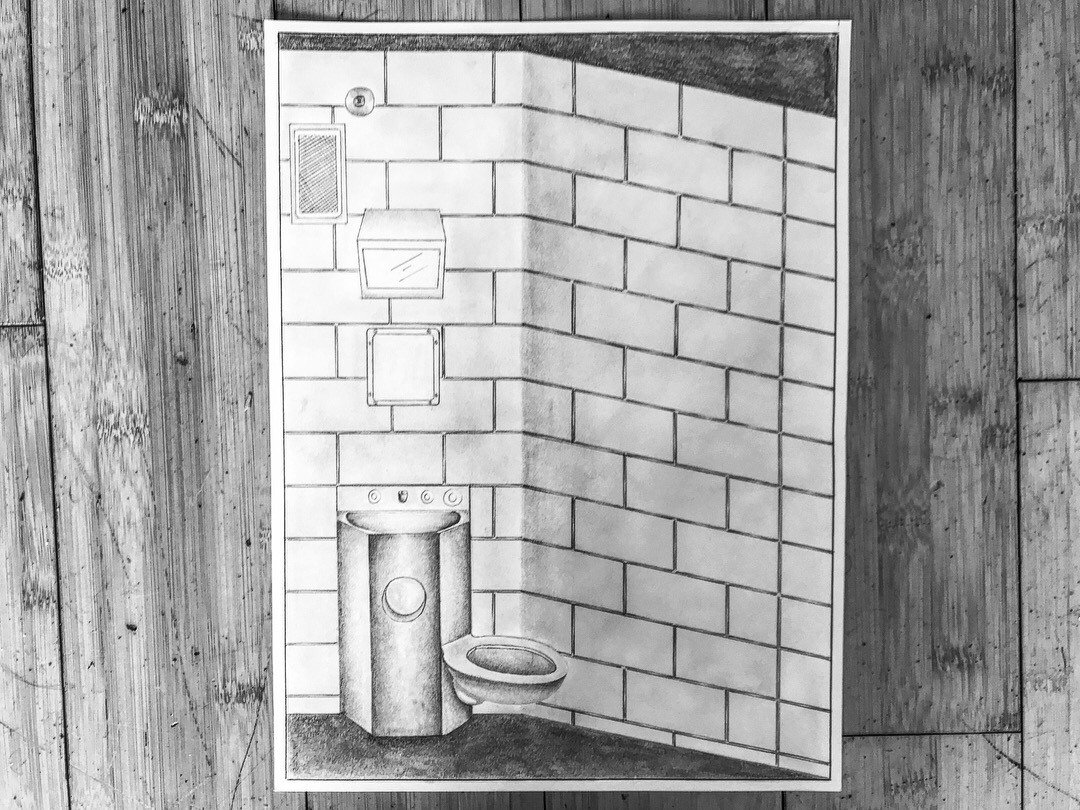

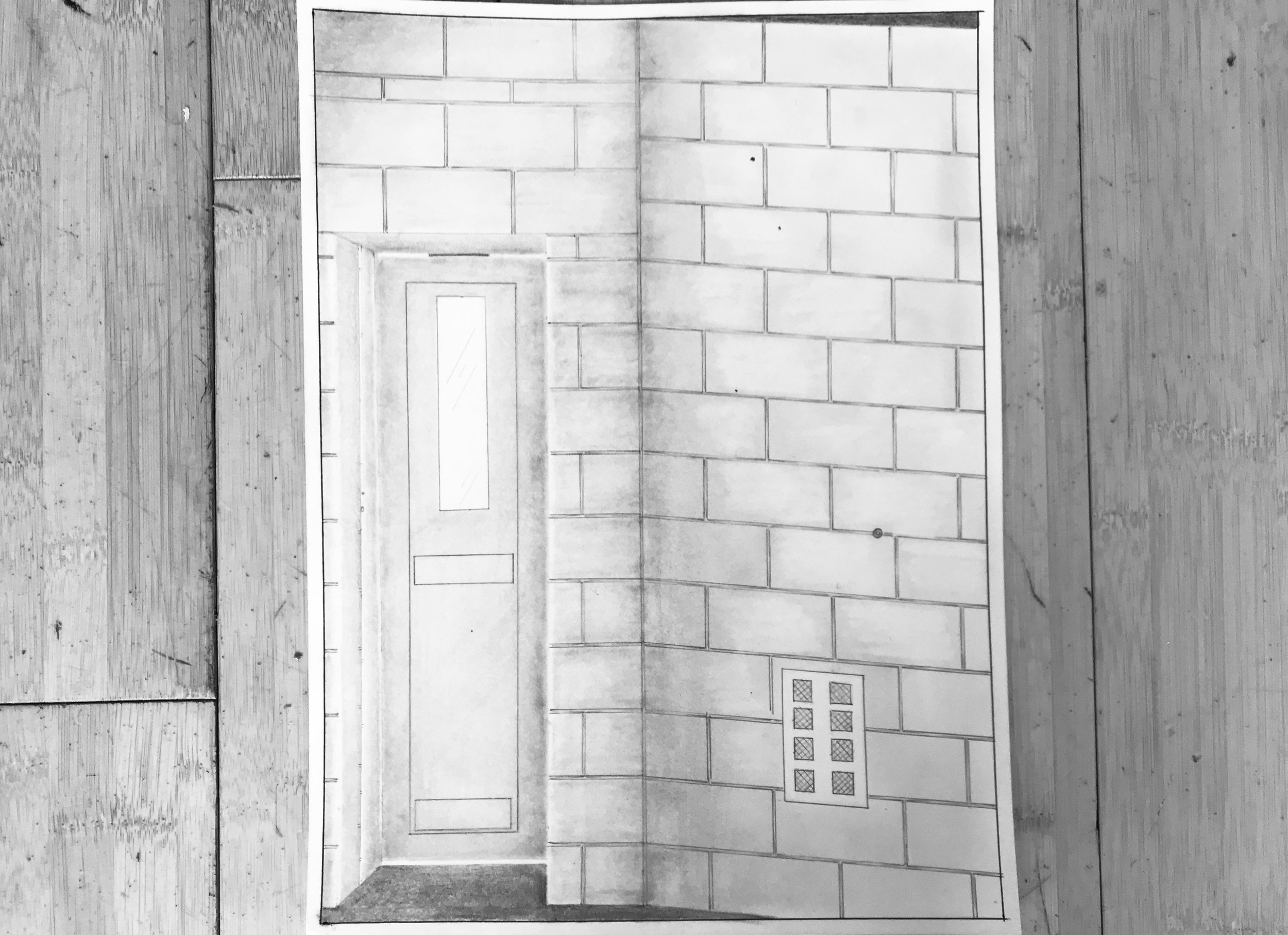

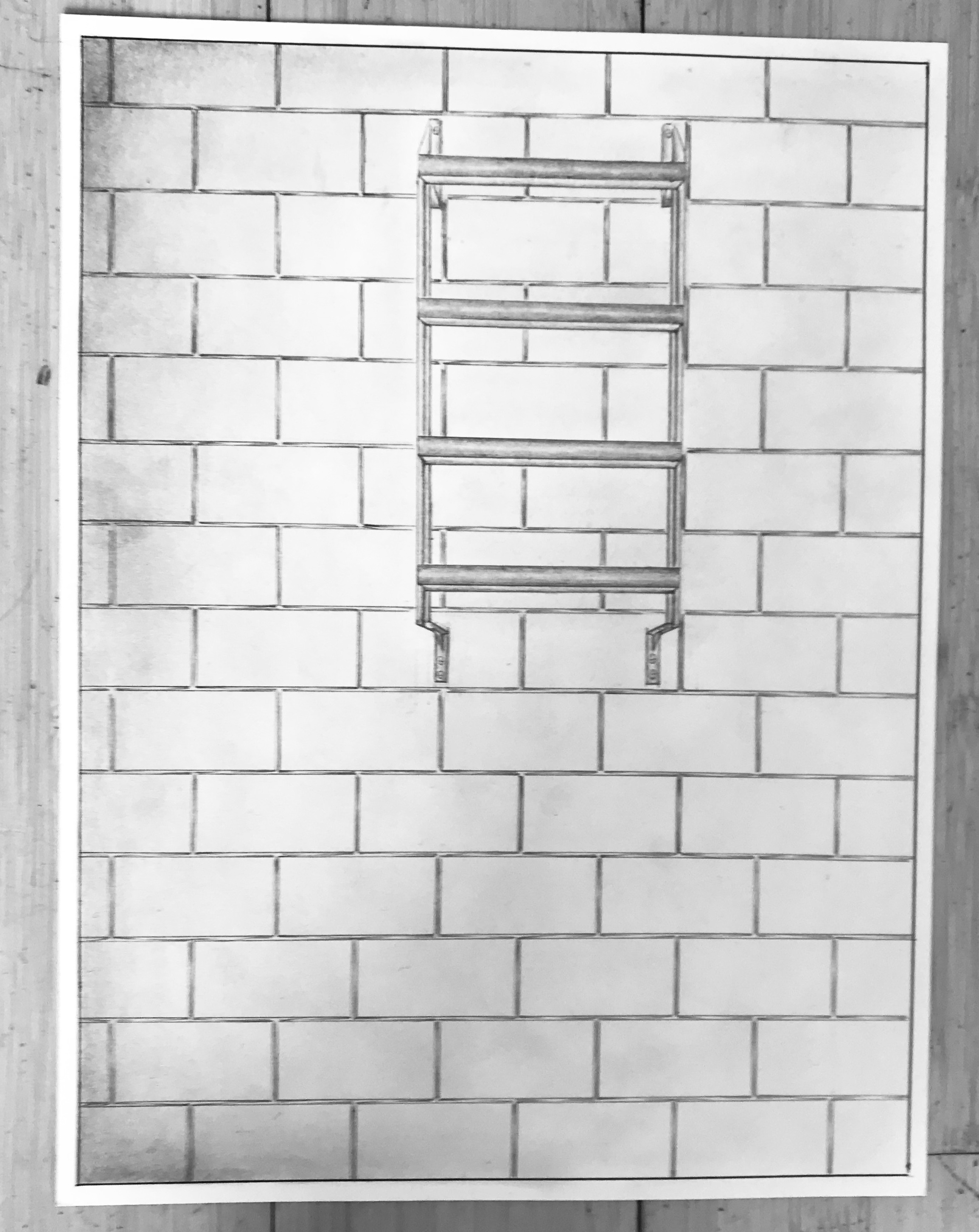

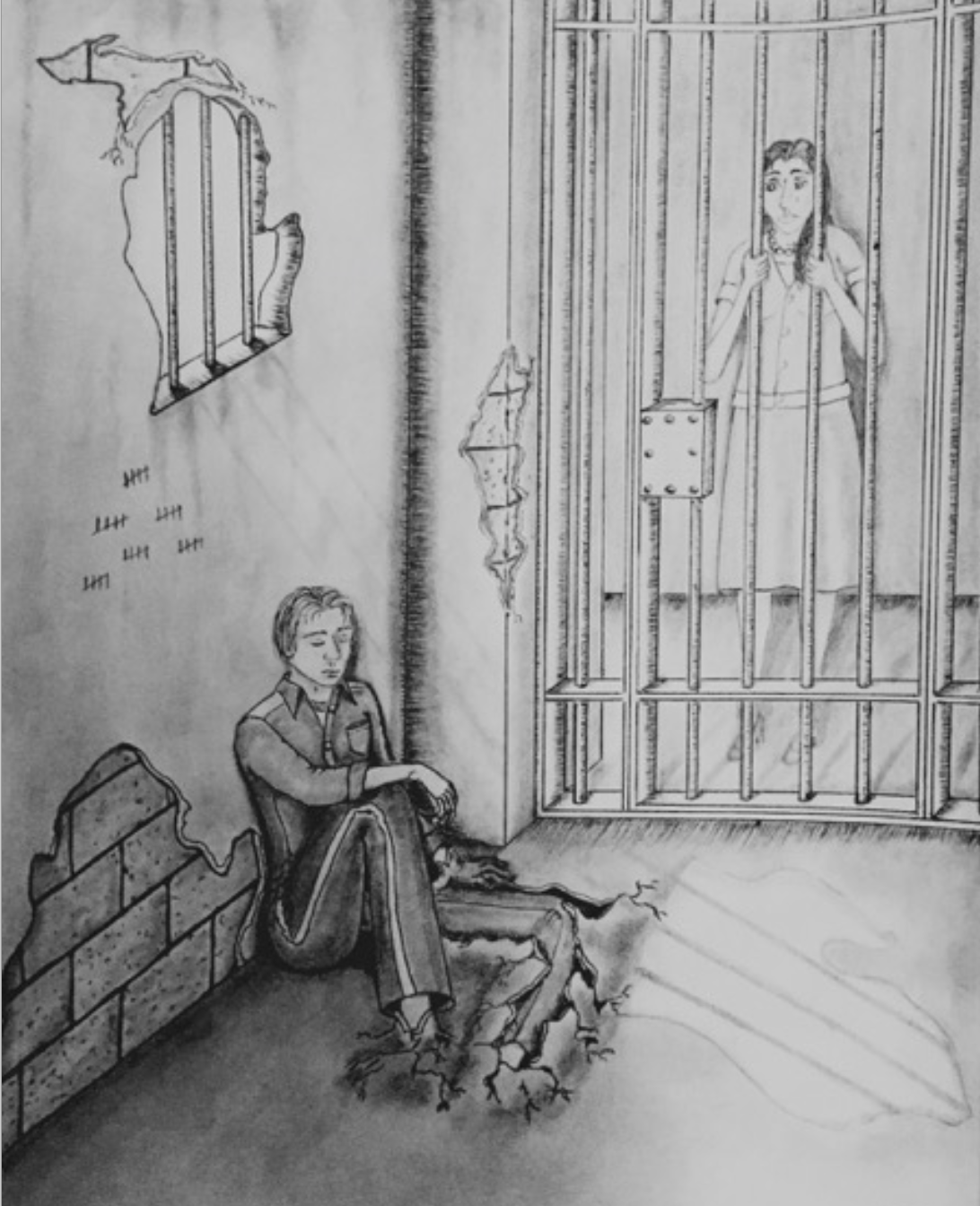

Artists: Jared Ritchie, Anson Ruiz, Joey Vang, Paul Rodriguez

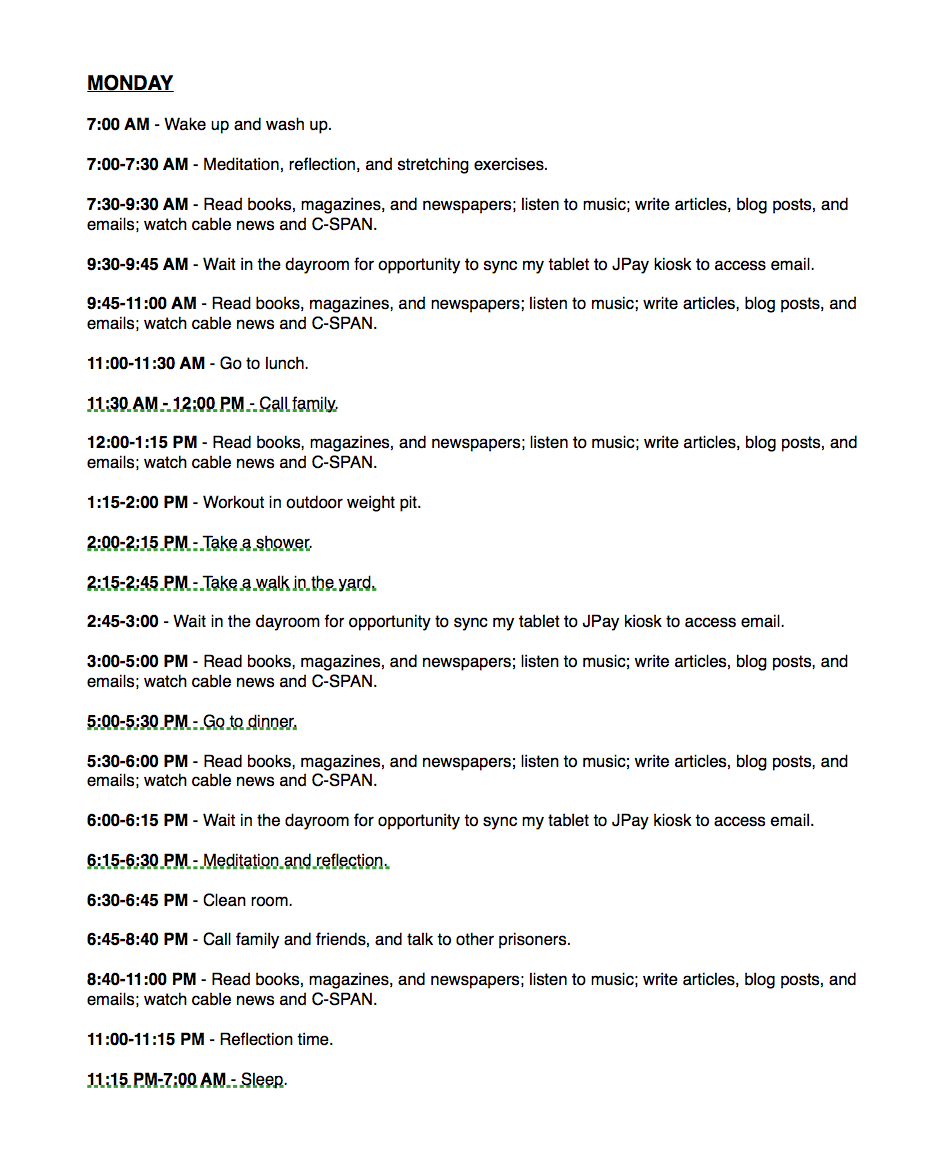

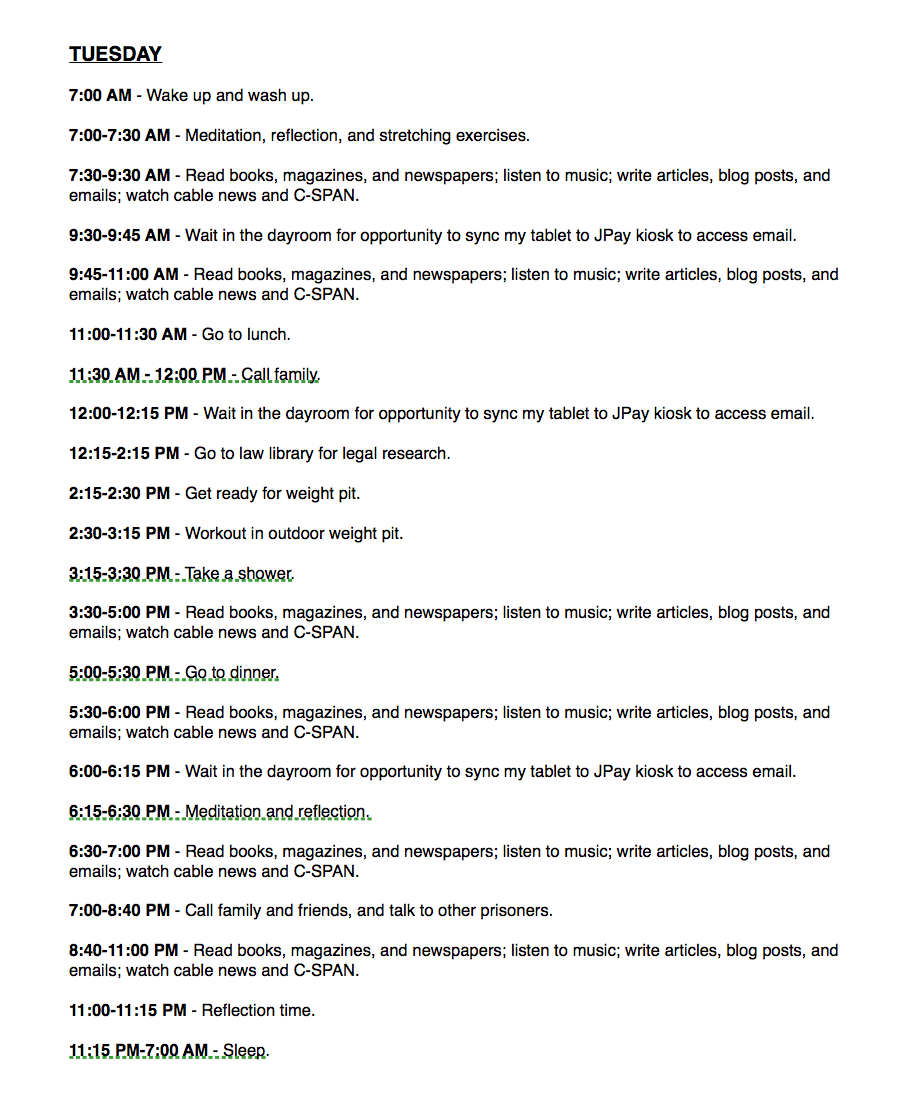

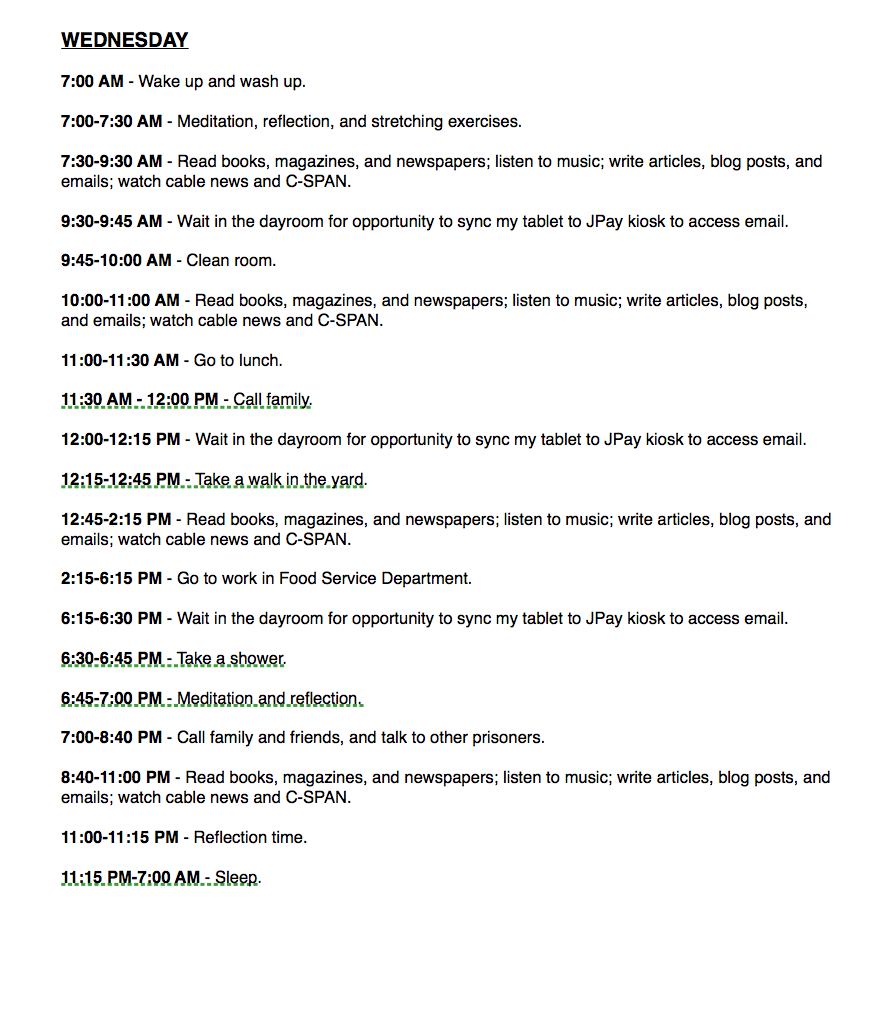

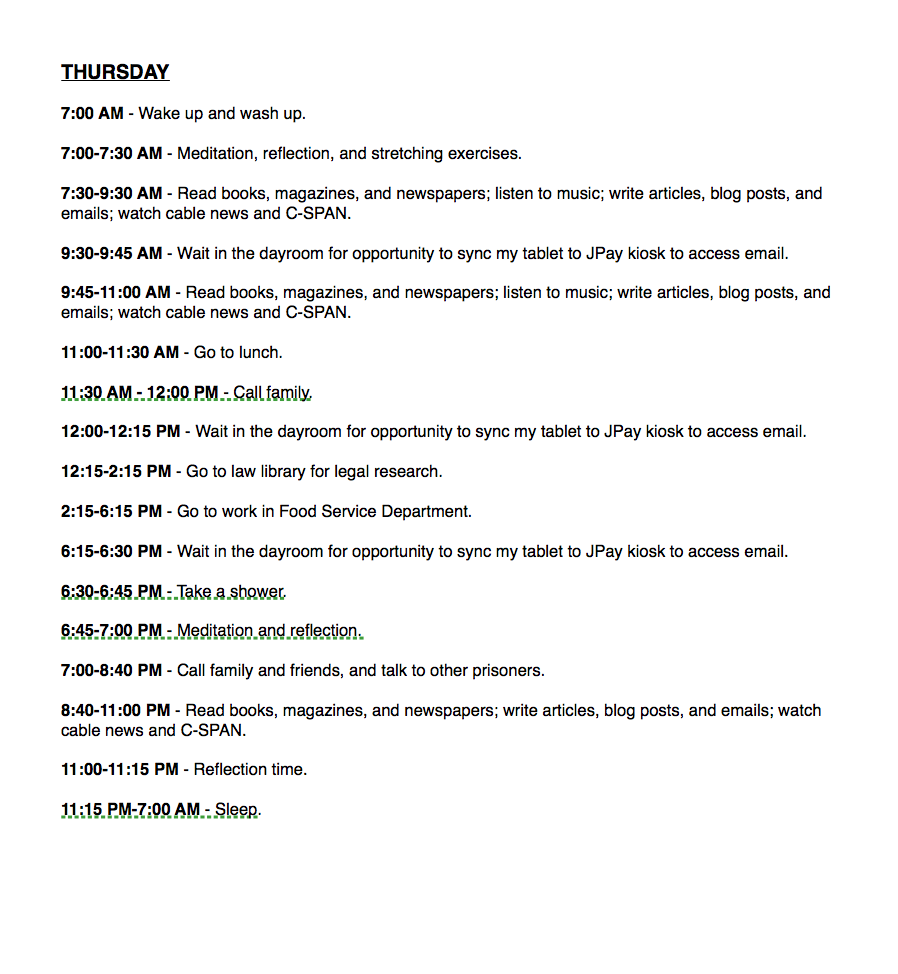

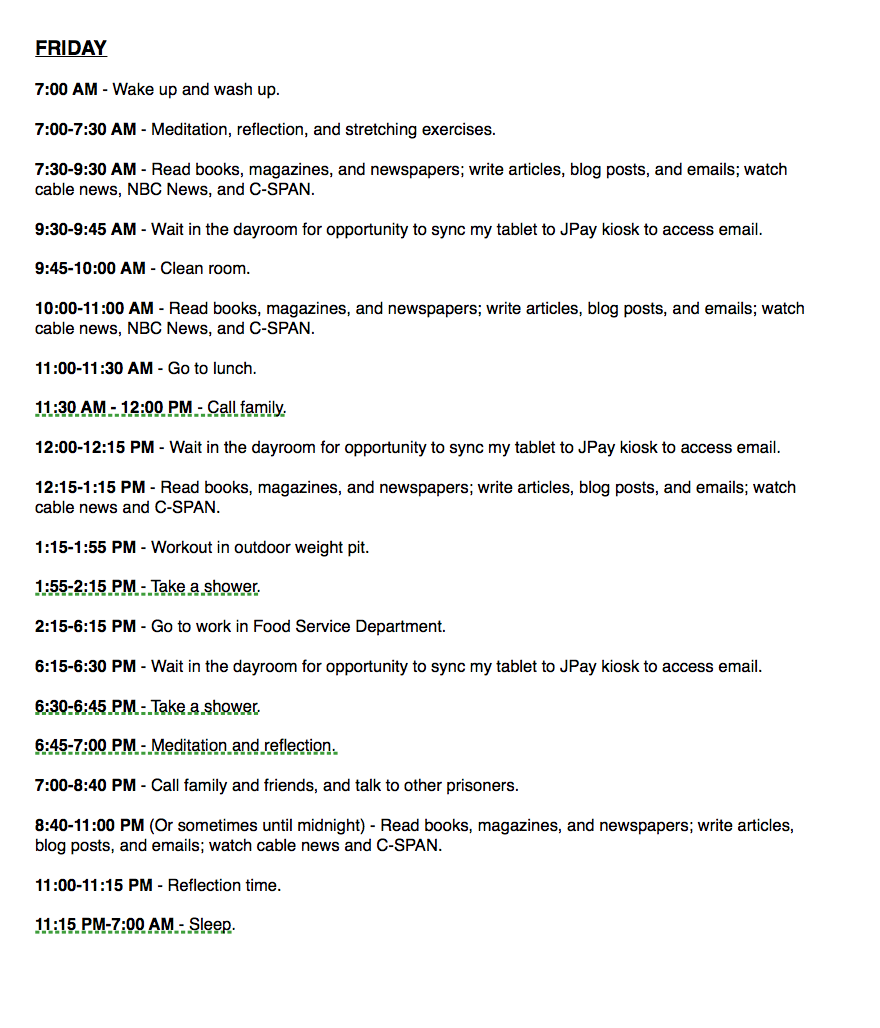

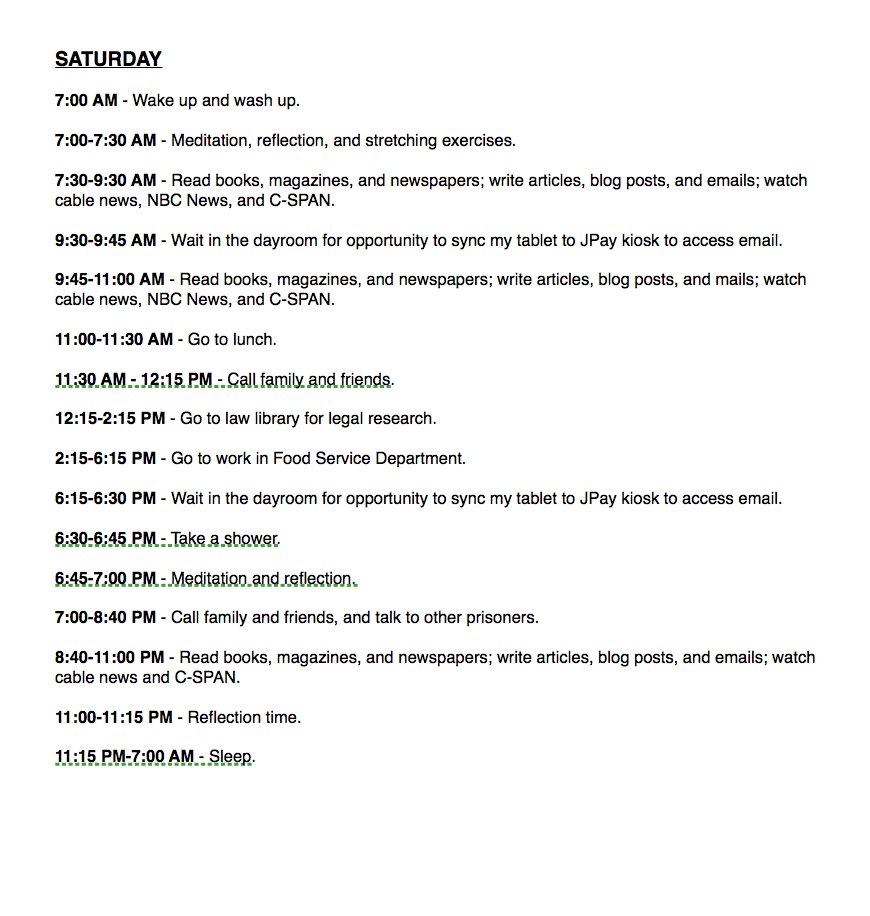

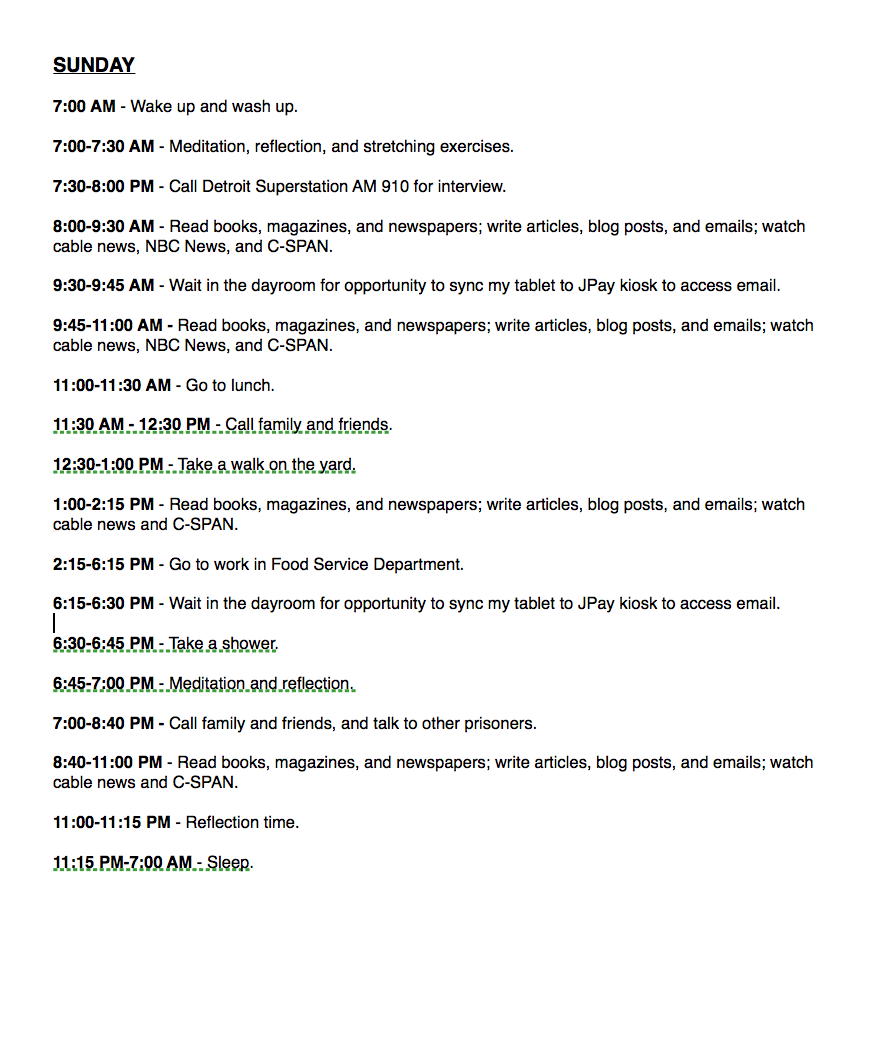

EFREN'S DAILY SCHEDULE

EFREN'S 10 POINT MICHIGAN PRISON REFORM PLATFORM

1. Abolish life without parole (LWOP) sentences for all juvenile offenders, revise MCL 769.25 to allow juvenile lifers to receive meaningful parole eligibility annually after serving 15 years, and allow juvenile offenders convicted under MCL 769.25 to receive good time and disciplinary credits, which is currently not allowed.

2. Restore good time eligibility so prisoners can earn early release for completion of rehabilitative programming and demonstration of positive behavior.

3. End Michigan's failed truth in sentencing policy which is largely responsible for maintaining a large prison population despite a widely recognized consistent statistical drop in crime for several years.

4. End mandatory minimum sentences and give discretion to judges to impose sentences based on all the facts of an individual case since no two cases are the same.

5. Institute presumptive parole for prisoners who complete all parole program requirements and screen high probability of parole so prisoners are not arbitrarily denied paroles they have fairly earned.

6. Stop sending women to prison who have been the victims of violence for defending themselves against their abusers.

7. Increase rehabilitative programming opportunities for all prisoner demographics, including those serving long sentences since 95% of all prisoners will become returning citizens one day.

8. Allow the Parole Board to obtain jurisdiction over prisoners serving long indeterminate sentences and begin annually reviewing them for parole consideration after they have served 20 years.

9. Allow prisoners serving parolable life sentences to become eligible for parole review/release annually after serving 20 years; and allow prisoners serving non-parolable life sentences to become eligible for parole review/release annually after serving 25 years.

10. Reduce the predatory pricing of prisoner phone calls from $.20 per minute to $.10 per minute to help prisoners maintain family and community ties and foster rehabilitation.

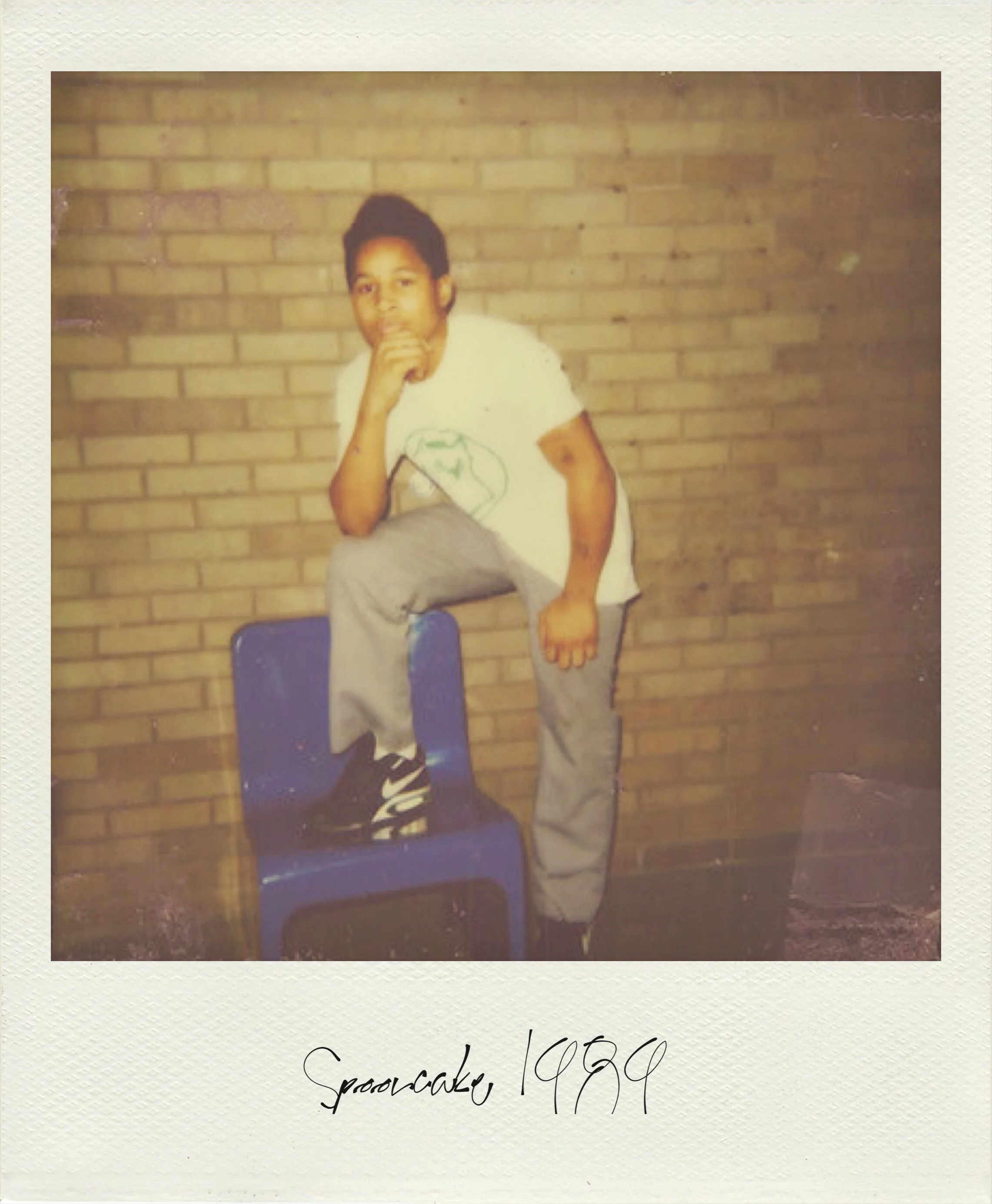

ADOLFO DAVIS (incarcerated October 1990 - today)

28 years ago,

Adolfo ("Spooncake") was convicted as an accomplice to the double murder of two men in a gang-related robbery. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole and maintains his innocence. Adolfo was 14 years old and the youngest person in Illinois' history to receive the sentence. There is no evidence to prove that Adolfo fired the gun. The night of the crime, Adolfo claims he was asked by two of his friends to be a lookout during the robbery of a rival drug gang, but that he was outside of the room, as a lookout, when the shooting took place.

Adolfo had a second chance to plead his case following Miller vs. Alabama in 2012 when the Illinois Supreme Court chose to apply the ruling retroactively. Yet, on May 4th, 2015, Adolfo was resentenced back to life in prison by Judge, Andrea Petrone. The trial was 11 hours long. Judge Petrone justified sentencing Adolfo to die in prison, citing a need to deter others from committing crimes and a responsibility to protect public safety,. To Adolfo, his family, and his lawyers, Judge Petrone’s dismissal of his maturation, and of how the circumstances he faced during his childhood could have influenced his behavior, came as a shock. To Adolfo, it seemed as if he was not even worth knowing, or understanding, in the eyes of Judge Petrone. It was as if he was irredeemable.

Demoralized, yet convinced he was destined to be free, Adolfo appealed the ruling. It was successfully overturned in the summer of 2017 by Illinois State's Attorney, Kim Foxx. Adolfo expects to be released by October 2020.

SPOONCAKE

is a soon-to-be released audio documentary about a man, who after falling through the cracks of the DCFS (The Department of Child Services) as a child, is struggling to create a world he can reenter after 30 years in prison. It features the voices of Adolfo, Shaboo (his auntie), and "Black" (his cellie). [Time 31:31]

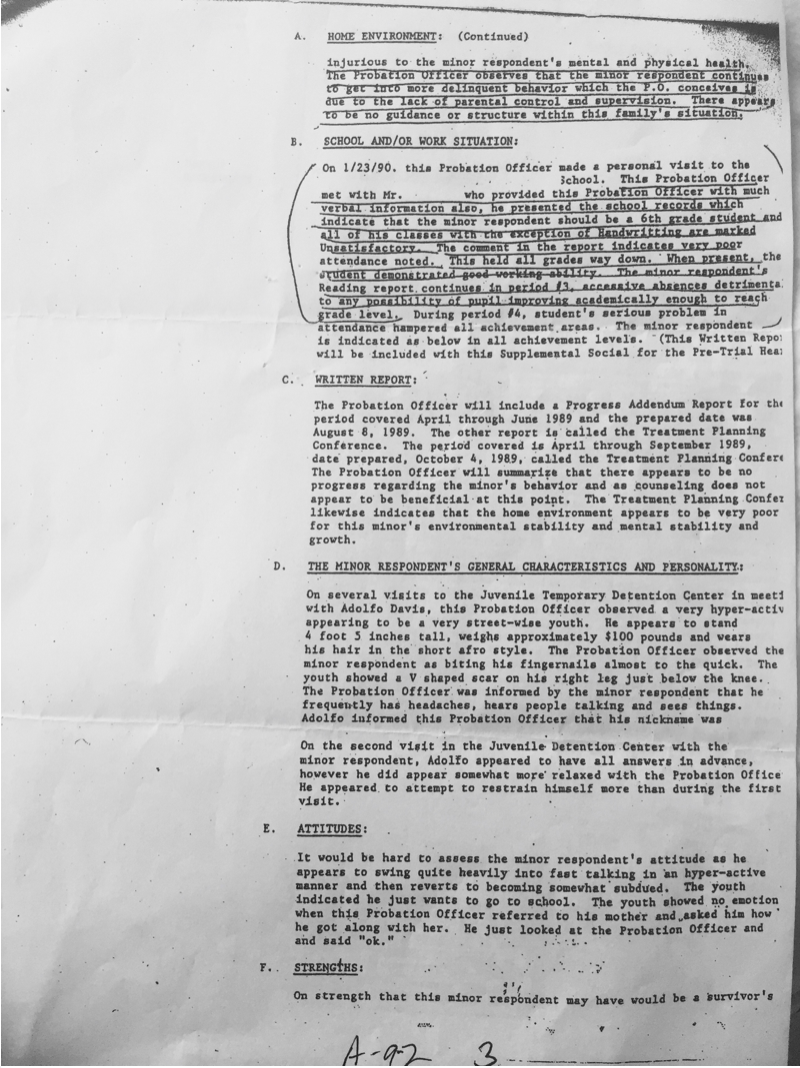

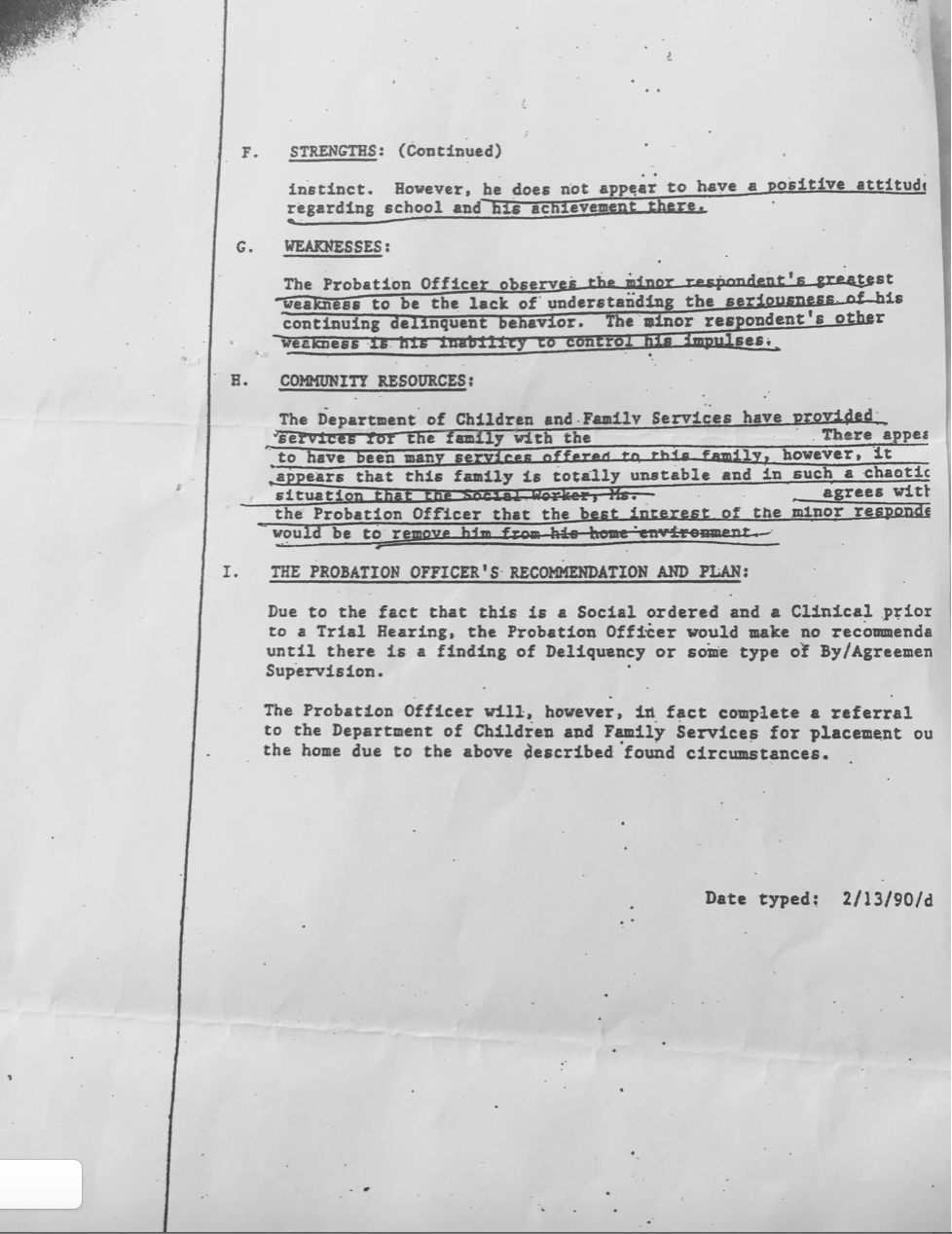

THE DEPARTMENT OF CHILD CARE SERVICES (DCFS)

These DCFS documents were sent to me from Adolfo. They date back to 1990, when the Department of Child Foster Services investigated the neglect and violence that Adolfo experienced in his home. Like many juvenile-lifers, Adolfo hopes to demonstrate the context surrounding his alleged crime. Adolfo’s decision to join a gang was not due to some inherent or incurable disposition for violence. Instead, Adolfo sought the protection and sense of belonging that the gang offered him.

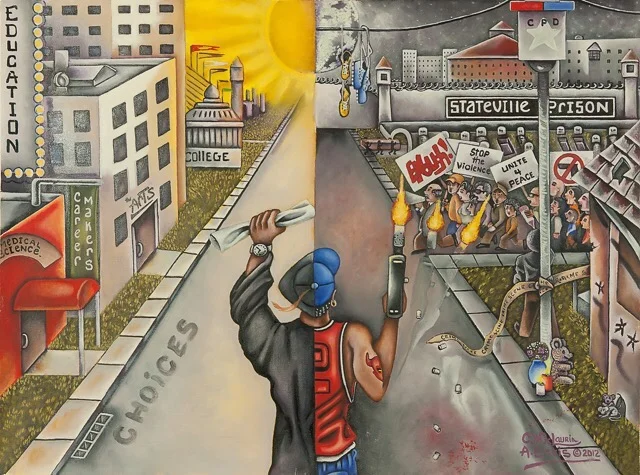

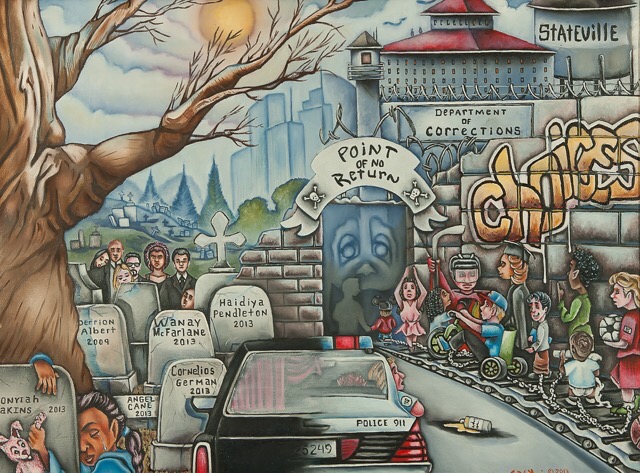

CHOICES

is a series of five paintings Adolfo created to represent the pressures he faced growing up on Chicago's South Side and to challenge the prosecutor's claim that his decision to turn to crime was actually a choice. After saving money to buy the paint, brushes, and canvas from the prison commissary, Adolfo painted this in collaboration with his cellmate.

In response to his erasure from the community, Adolfo sought to reveal the inner world that he has cultivated while incarcerated through his art. To tell his story, Adolfo created a series of paintings, titled “Choices”, in collaboration with his former cellmate, Charles McLaurin, who is serving a life sentence. Drawing from memories of his childhood growing up on Chicago’s South Side, Adolfo wanted the paintings to depict the consequences of living in a world where choices are a privilege, not a right, and to serve as a warning to youth of “all the things that might happen to you if you make the wrong choices”.

Adolfo takes responsibility for the choices he made, yet he also believes that the agency to be able to make decisions about one’s own life cannot be isolated from one’s reality. Adolfo portrays this by dividing the first two paintings of the series (Drop Out, Natural Life) into two sides: the left side represents the choices that he wished he could have had, such as attending and graduating school, in a world that protected him and believed in him; the right side: the choices he made growing up as a black boy, in violent and isolated neighborhood, in a world that dismissed him, segregated him, and punished him.

Adolfo gave the paintings as a gift to Father David Kelly, executive director of Precious Blood Ministries and Reconciliation. Kelly met Adolfo in 1989 at the Audy Home (Juvenile Detention Center). Since then, Kelly has mentored and visited Adolfo. When Adolfo is released, he plans to work with Kelly as a support person for youth who are at risk of incarceration or victimization.

NEVER HAD A CHANCE

is a story Adolfo wrote (in a series of letters from prison) about his childhood to demonstrate how the State's failure to protect him from a violent and unstable environment led it to punish him, and ultimately sentence him to die in the most violent place he can imagine -- prison.

Dear people and representatives of Illinois,

My name is Adolfo Davis. I’m 40 years old. I was born in Chicago, Illinois, but raised in the Illinois Department of Corrections. I have been incarcerated since I was 14 years old and I am currently serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. Since I can remember, my life has been unstable and chaotic. By the time I was 14 years old, I lived in 11 different places. I lived with my aunt and my uncle until my grandparents had their own place. I lived with them along with 10 other family members in a 2 bedroom apartment.

There was a lot going on in those apartments. My grandfather was dying and he knew it. So he drunk bottles of Red Irish Rose all the time. One of my uncles was mentally unbalanced and had fits all the time. Then there was my mother, who loved drugs more than she loved her own

kids. She would drink, smoke squares and weed, do cocaine, and then when crack came out, that became her first love. One day I walked in on her doing crack. I still have that vision in my head. There was always fighting and no food in the house. My grandmother did everything she could to take care of everyone, but it was just too much for one person. She was my heart. She and my little brother were the only 2 people that I can say I loved. But, I knew at an early age that I had to take care of myself.

By the time I was 8 years old I turned to the streets. I wanted to get away from that sadness, pain, and stress that was in my household, but I also had to find a way to take care of myself. I needed to find some kind of peace and place to belong. So, I started doing whatever I could to eat and get clothes. I pumped gas, carried groceries, stole food out of stores, and even stole people’s clothes when they hung them out to dry. I even waited until KFC closed to get the food they threw out. I did what I could to eat.

One day while I was pumping gas, four guys came to the gas station and asked me who I was and said that that I owed them for pumping gas at their gas station. I tried to run but I slipped and they jumped me and took my money and my transformer radio. I slipped because I had on some penny loafers. But, the next day, I was ready because I wore some gym shoes that I bought from Good Will. To avoid them, I went earlier, but they showed up again. Before they said anything, I said that I didn’t want any trouble. I pretended to go into my back pocket to get money for them, but they didn’t know that I had a surprise for them. I took out one of my grand-dad’s Red Irish Rose bottles and threw it at them. When they covered their heads, I took off running. That day, no one was going to catch me. I ran like I could have been on a relay team.

I knew I couldn’t go back to that gas station, but that was the only way I could make money fast. So I decided to go back, but that I would go there at 5 in the morning. The gas station was like 5 blocks away from where I stayed and I had to walk by gangs to get there, but they never messed with me. When I got to the gas station there were a lot of cars there so I started pumping as. A lot of people would ask me what I’m doing at that time of the morning and I told them the truth. Some of them would buy me food or candy sometimes. So everyday I got up at

4:30 to 5 AM and went to the station. I realized that was the best time because people were off to work. About a week went by before this old man who was selling newspapers came up to me and asked me if I wanted to help him sell newspapers. So I did. His newspapers went fast so I still had time to pump gas before them guys showed up.

One day, I went to work to pump gas and sell newspapers, but I was too tired to work. So I stayed for like 30 minutes and started walking home. Then I saw this church that I passed al the time. It had a wheelchair ramp that went to the basement. So I went down there and went to sleep, only to be wakened a few hours later by this old lady. She shook my leg, and I opened my eyes to see her and about 10 kids. She asked me why I was sleeping right there and said, don’t you know that you could get hurt or killed? I told her the truth. She asked me if I was hungry. I said, yes.

She took me in the church and fed me. She was the Sunday school teacher and the kids I saw earlier were there for Sunday School. After Sunday School, she took me home to my grandmother and told her how she found me. She asked her if it was okay if I hung out at the church with her and my grandmother said yes. My grandmother was happy someone was going to be looking out for me. The lady brought food to my grandmother once a week, but she died a month later.

After she died, I never went back to church. I went back to pumping gas and selling newspapers. One day I was inside when the guys I got into it with at the gas station walked in. They didn’t see me at first, but I saw them, and I was ready. When they saw me, one of them said, “We been looking for you. Come outside so we can talk to you”. I told them “I’m not going out there so you can jump me”. They responded, “We can jump you in here”. When I went outside, they asked me my name and if I wanted to hang with them, and I said “yeah”. That day, I found my family.

When I got to know them, I saw that they story was like mine… mother on drugs, father in an out of our lives, and our grandmothers were holding down the families. So we connected. We became family. We did everything together. We stole together. We ate together. We protected each other and we understood each other’s pain. We used to go downtown to the union station and breakdance, shine shoes, and steal. Whatever we made we shared with each other. I belonged.

One day, we were pumping gas, but it was slow so we didn’t make any money. I was so hungry, but I knew there wasn’t going to be any food at home. So when I saw this little girl coming out of the store with a bag of food, I tried to take it, but she held on the bag and took off running. 3 dollars worth of food stamps and 75 cents fell out of her hand. I picked it up and went and bought something to eat. A few days later, I was arrested for strong arm robbery. I didn’t know my address and we didn’t have a phone, so at 12AM they sent me to the Audy Home (The Cook County Temporary Juvenile Detention Center) because no-one came to pick me up at the station. I was a little scared about going to the Audy Home because of all the stories I heard. When I got there, they asked me if I have anyone to call, but I didn’t. So they took me upstairs to healthcare to get a check up. Then I was sent to the unit. It was dark because all the lights were off and I was the only one out. Everyone else was in their rooms. The staff in the unit gave me a towel, some soap, and told me to take a shower. Once I was done with the shower, they gave me something to eat. Once I was done, he locked me in a room and I went to sleep. When I woke up, I ate breakfast and went to court. Then I was released.

When I got to court, I saw my grandmother. The only reason she knew that I was locked up was because my friends had told her. When I got home, no one cared what happened to me except my lil’ brother and my friends. My friends asked me if I was okay and what it was like to be locked-up? I was the first one from our crew to go to the Audy home and it was the first time in my life that I had my own room. There, I truly felt safe and protected.

So, I started getting into more trouble and the Audy home became my home. That was the place for me. I had my own room. I ate 3 times a day and didn’t have to steal, rob, sell drugs, or worry about where my next meal will come from. The staff was cool and I was happy there. I missed my grandmother and lil’ brother, but at the same time I knew my being there took a lot off of her because she knew that I was safe. I went there 8 times in total. When I first went, in 1987, I was 10 years old. From the ages of 10 to 14, I was arrested 21 times.

My grandmother asked for help form DCFS and the judge. She asked both to remove me from her custody, but nothing happened. All DCFS did was check in on us. Their own report said my household was ‘chaotic and unfit to live in’, but they still kept me there. They also sent me to

see a psychologist, but he didn’t listen to me. He just diagnosed me with what he wanted to be wrong with me. So I stopped sharing my thoughts with him and just agreed with what he said in order to get out his office. I felt that the system didn’t care because they kept me in a household where I didn’t want to be.

When I was 12 years old, my friend’s big bothers asked me and my friends if we wanted to make $250 a week to be a lookout while they sold drugs. We all agreed. The next thing I knew we were in a gang. I was so happy. $250 each week was the best thing that ever happened to me. On top of that, they had a spot we should chill and eat. They protected us and people respected us. I finally had the family I searched for, but the false reality I was living, eventually took my life. But at the time, I was able to take care of myself, my lil’ brother, and help my grandmother. That life was the best, but it came at a price. Two of my close friends were killed.

When I was 13 years old, I was robbed with a friend of mine. That night, I thought I was about to die and I welcomed it. I didn’t care if I lived or died. So I just closed my eyes when the guy put the gun to my head. I knew my mother and father didn’t care and that it would have taken a burden off my grandmother. I thought maybe death would be better. Those were my thoughts as a youth. After the robbery, we found out that some of our own friends had robbed us. In all this, The Audy Home was the only place I found peace.

About a month later, I was hanging with a friend while he was selling drugs. I was waiting until he was done because the police pulled up. We didn’t run because the drugs were hidden. So we thought we were cool. The police put us in their car and while we were sitting in the back seat of the police car, an old lady came out of her apartment and showed the police where the drugs were. When the police came back with the drugs from the spot he had them my friend started crying. He said he couldn’t go to jail. He was 17 years old and crying like a baby. So I told him that I would tell the police that it was mine, but that he would have to pay me when I got out. So I lied to the police and went back to the Audy Home. It was August 22, 19990.

Then, I was released into DCFS’ custody on October 1,1990. I was happy because I thought that I was about to get a good family, but that afternoon I was taken to a shelter instead. When I got there, I was put in a small room with about 20 other kids watching tv. All they fed us was popcorn. Then they put me and a few of the other kids in a van and took us to one of DCFS’ placement homes to sleep. In the morning, they took us back to the other shelter and gave me a room upstairs. But, two days later I ran away. Five days later, on October 11, 1990, the crime that I’m incarcerated for now happened.

This has been my nightmare for the past 28 years. Since birth my life has been a struggle.

I never had a chance.”